You’re not going to beat Steph Curry in a game of horse. Indeed, through three games, Curry has made more pull-up triples (14) than the entire Boston Celtics roster (10). Yet as far as total 3-point shooting goes, the teams have 49 makes apiece. The Celtics have to work harder for their shots, have to leverage more and more diverse abilities, than Curry for the Warriors; they can’t just throw the ball at the hoop whenever, from wherever, and expect success. Much of Boston’s offense — even their 3-point shooting — is unlocked every time Jaylen Brown drives to the rim.

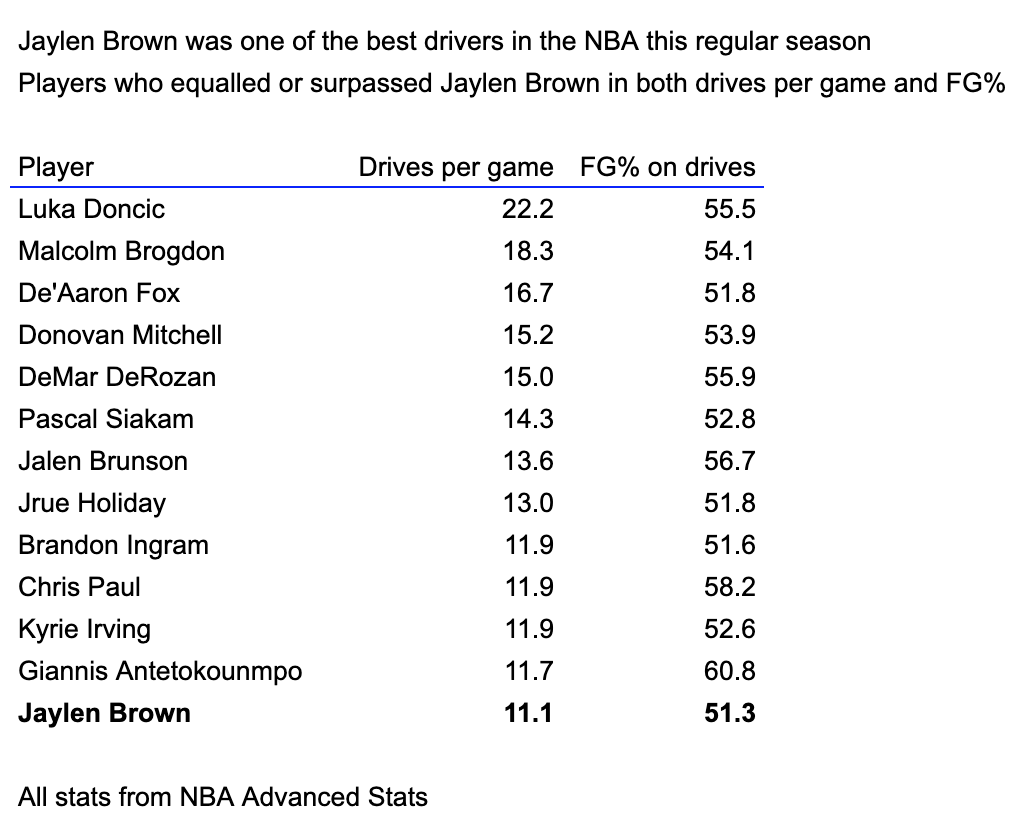

There aren’t many players who can attack the rim as frequently and as efficiently as Brown. He has gigantic hands, a huge vertical leap, and a monstrous, 7-foot wingspan, and those abilities stand him in good stead when he reaches the paint. In fact, only 12 players managed to equal or surpass him in drives per game and field goal percentage on those drives.

The majority of the above players are initiating guards. In fact, the only players on the list who used fewer possessions as pick-and-roll handlers than Brown were Antetokounmpo and Siakam. That means most players on the list saw their drives come from actions they initiated; less so for Brown. Moreover, he averaged fewer touches than any other player on the above list. All this to say, Brown did an enormous amount of driving in the regular season without a comparable rate of touches, either in the pick and roll or elsewhere. Instead, he attacked the paint against rotations, closeouts, and other scrambled sets. He maintains advantages created by his teammates at a rate comparable to the best in the league — the other driving leaders did so more often to create advantages rather than convert them.

That ability is crucial for the Celtics’ offense. Brown shot 76.5 percent at the rim in the regular season — if he reaches the paint, it’s basically death for a defense. He also happens to be one of the league’s best at reaching the paint.

So how has that impacted the Finals?

When Brown has driven the basketball, the Celtics have won. Through three games, it has been that simple. In Game 1, Brown drove a staggering 18 times, and the Celtics won. In Game 2, Brown drove only six times (one off his fewest on the season), and the Celtics lost. In Game 3, he drove 12 times, and the Celtics won.

Meanwhile, Curry is playing horse, and the Celtics in many ways haven’t been able to match him. He’s averaging 31.3 points per game while shooting 46.7 percent on pull-up threes — supposed to be one of the most difficult shots in basketball. Golden State’s offense has been consistent, scoring between 100 and 108 points in all three games. Curry is a known quality, and the Warriors are riding on his back.

In many ways, Brown is behind the wheel for the Celtics. In wins, they’ve scored 120 and 116 points. In their lone loss, they scored only 88. Boston’s offense is significantly less consistent. They can’t match Golden State by hitting circus shots worth three points over and over, let alone finding seven point possessions. But what they lack in consistency they make up for in sheer ceiling — this offense can arguably punch above the Warriors’, even if they can’t hit the same type of impossible shots.

The Celtics are thriving on solid, replicable offense. Brown creates simple shots. He is an outrageous finisher, capable of leaping over anyone and finishing violently or softly.

But so too is he able to create for his teammates. Because he’s such an incredible finisher, he draws gobs of attention as he romps through the lane. That opens the floor for interior passes to teammates for layups or kickout passes for triples. The Warriors may not roster Curry, but they can match him as long as they’re firing set shots like this.

Boston is outshooting Golden State in the Finals, and the Celtics are doing it by playing a different game. Rather than copying Curry, they’re selecting easier shots. Boston is attempting more catch-and-shoot triples than Golden State and making them at a higher rate. It’s not hard to win a game of horse when your opponent is flinging up prayer after prayer and you’re allowed to answer with set shots.

That system doesn’t work without Brown driving the basketball. The Celtics don’t create layups without Brown, and they don’t create open triples without the threat of layups. In both wins, they’ve attempted more layups than the Warriors and made shots at the rim more efficiently. Brown is crucial there. He’s just as important in making sure the Celtics are humming from deep, too.

Brown isn’t necessarily Boston’s best offensive player. That distinction likely goes to Jayson Tatum, who has led the entire Finals in touches. He is the advantage creator, the isolation and pick-and-roll leader. He forces the defense to rotate, to blitz, to alter its shell. Tatum is the engine. But Brown is the piston. Tatum creates for the team, summoning kinetic energy out of thin air. Brown converts it into work, into layups and triples, into offensive force. Both engine and piston are necessary components for the proper function of a vehicle. And with the Warriors increasingly running a switch-to-blitz system, or initially switching screens before sending a second defender to the ball to gum up the action, Boston’s second-side attacks will be increasingly impactful. Translation: Brown will have a larger part to play.

In some ways, the Warriors have lacked that same healthy offensive ecosystem. They don’t have a slasher as thorough as Brown who can distribute advantages into easy points. They have subsisted instead on heroics. And Curry has, in many ways, delivered. But the Celtics have overpowered him, and they’ve done it with simplicity. It’s good to be the fastest, the biggest, and the most athletic. Brown is learning just how far those abilities can drive him.